Marjorie Harding

Marjorie Gladys Harding was born on October 24th 1922 in Walsall, Staffordshire. At an unknown point during the Second World War she moved to Tenby, Pembrokeshire where she lived for the rest of her life.

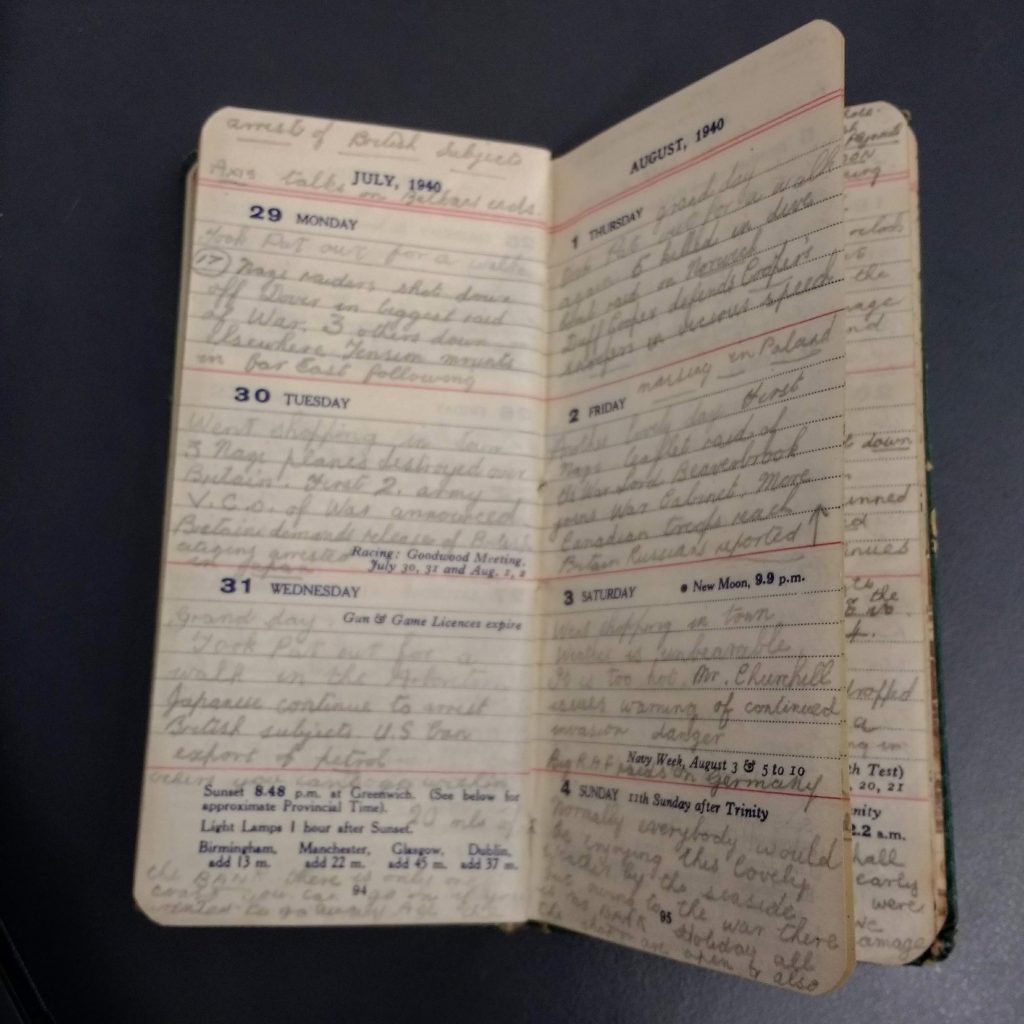

Marjorie’s teenage diary from 1940 provides a unique insight into the milestone events of WWII as they unfold. She begins the year with a tone of distant anticipation; keeping detailed records of military losses alongside lists of the books she has been reading. Her ‘Balance Sheet of Casualties’ from September 1939-40 has a column for British troops (92,000) and a column for Germans (where she estimates more than 500,000 deaths). She meticulously breaks the losses down into sub-categories including ‘Destroyers, Submarines (and) Battleships’ and is very much a detached observer. Over the page, she lists her shoe size as ‘4’ and some of the romantic novels she has read, (including ‘Enchanted Wilderness’ and ‘Wend among the Blossom’), again, in the tone of an enthusiastic collector.

As we delve deeper, Marjorie’s diary soon begins to show the impact of war on the lives of ordinary people. She mentions a ‘shortage of potatoes’, then a ‘shortage of coal’, compounded by the ‘severest winter weather in living memory…(which) brings war to a standstill’. At home she says ‘All our taps, except scullery, are frozen up…went into town to get Mrs. Cooper a rabbit. No English meat about, only frozen. So of course, rabbits rose to 2/- each’. (27th January 1940).

On one level, Marjorie Harding’s diary reads like a timeline of historically significant events. On 9th April she writes: ‘German forces invade Norway and Denmark in early morning. Denmark succumbs in 12 hours’, 10th May: ‘Germany invades Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg before dawn’, 4th June: ‘Mr. Churchill reveals that more than 300,000 troops have been evacuated from Dunkirk’. Nevertheless, the diary also raises many questions about Marjorie’s life and is often both poignant and humorous.

It is not clear how Marjorie received all of the detailed information she shares in her diary. Despite being just 18 years old, she clearly has a fastidious interest in statistics and current affairs and is mature and perceptive. However, she states that ‘the wireless and the papers do not tell you much’. It is possible that she receives information from her father who was a ‘Licensed Victualler’ and possibly sold provisions to the army. As such, he may have had anecdotal access to information. Nevertheless, it is the increasing impact on Marjorie and her family that is most compelling and insightful.

As 1940 progresses, Marjorie’s handwriting becomes more rushed and her tone becomes more personal. She describes frequent air raids that ‘shook our house’ and we gain a real sense of urgency and terror. On 28th August she writes: ‘They were here again as soon as it was dark this evening, for another 6 hours. We have made a makeshift bed up in the hall’. On 24th October she poignantly writes : ‘I shall remember my birthday- 8.20 sirens went…they were here a little time but did a lot of damage. Some of the bombs ever so near’.

By Christmas, Marjorie’s handwriting appears childlike and the description is sparse: ‘Went to try to do some shopping. Not much you can get these days…’ followed on Christmas day with ‘Spent very quiet Xmas at home. No sirens’. However, Marjorie Harding’s diary is not without humanity and humour. Dates are circled in monthly increments that presumably mark her menstrual cycle and she makes frequent reference to her sister Betty, exclaiming on 13th April: ‘Betty has had her hair PERMED’. Furthermore, light relief from the horrors of war comes in the form of shopping trips, Betty’s acceptance into college and, on 7th March, a trip ‘to the pictures…to see Shirley Temple in Suzannah of the Mounties’.

Throughout her diary, Marjorie Harding refers to her days as ‘quiet’ and containing ‘nothing of importance’. However, history reveals just how significant her words have become as a personal insight into an era that will never be forgotten. Not much is known about her life in Tenby after the war, except that she died in 1997 in South Pembrokeshire.

Ganed Marjorie Gladys Harding ar Hydref 24 1922 yn Walsall, Swydd Stafford. Rywdro yn ystod yr Ail Ryfel Byd symudodd i Ddinbych-y-pysgod, Sir Benfro lle bu’n byw am weddill ei hoes.

Mae dyddiadur Marjorie yn ei harddegau o 1940 yn rhoi darlun unigryw i ni o’r digwyddiadau wrth iddynt ddigwydd oedd yn garreg filltir yn yr Ail Ryfel Byd. Mae hi’n dechrau’r flwyddyn yn eithaf gobeithiol; yn cadw cofnodion manwl o’r colledion milwrol ochr yn ochr â rhestrau o’r llyfrau yr oedd hi yn eu darllen. Yn ei ‘Mantolen o’r Meirw’ o fis Medi 1939-40 mae colofn ar gyfer milwyr Prydain (92,000) a cholofn ar gyfer yr Almaenwyr (lle mae’n amcangyfrif bod mwy na 500,000 wedi’u lladd). Mae hi’n rhannu’r colledion yn ofalus yn is-gategorïau gan gynnwys ‘Dinistrwyr, Llongau Tanfor a Llongau rhyfel’ gan roi sylwadau eithaf gwrthrychol. Dros y dudalen, mae hi’n rhestru maint ei hesgidiau fel ‘4’ a rhai o’r nofelau rhamantus y mae wedi’u darllen (gan gynnwys ‘Enchanted Wilderness’ a ‘Wend among the Blossom’), sydd eto yn sylwadau casglwr brwd.

Wrth i ni ymchwilio’n ddyfnach, buan y mae dyddiadur Marjorie yn dechrau dangos effaith rhyfel ar fywydau pobl gyffredin. Mae hi’n sôn am ‘brinder tatws’, wedyn ‘prinder glo’, a wnaed yn waeth gan y ‘tywydd gaeafol gwaethaf mewn cof… sy’n dod â’r rhyfel i stop’. Gartref, meddai ‘Mae pob tap yn y tŷ, ac eithrio yn y sgyleri, wedi rhewi … ês i’r dref i gael cwningen i Mrs. Cooper. Dim cig ffres yn unman, dim ond cig wedi’i rewi. Felly wrth reswm, cododd pris cwningod i 2/- yr un’. (27 Ionawr 1940).

Ar un lefel, mae dyddiadur Marjorie Harding yn darllen fel llinell amser o ddigwyddiadau hanesyddol arwyddocaol. Ar 9 Ebrill mae hi’n ysgrifennu: ‘Milwyr yr Almaen yn ymosod ar Norwy a Denmarc yn gynnar yn y bore. Denmarc yn ildio mewn 12 awr‘, 10 Mai: ‘Yr Almaen yn ymosod ar yr Iseldiroedd, Gwlad Belg a Lwcsembwrg cyn y wawr’, 4 Mehefin: ‘Mr. Churchill yn datgelu bod mwy na 300,000 o filwyr wedi eu symud allan o Dunkirk’. Serch hynny, mae’r dyddiadur hefyd yn codi llawer o gwestiynau am fywyd Marjorie ei hun, ac mae’r sylwadau yn aml yn ingol ac yn ddoniol.

Nid yw’n glir sut y derbyniodd Marjorie yr holl wybodaeth fanwl y mae’n ei rhannu yn ei dyddiadur. Er mai ond 18 oed oedd hi, mae’n amlwg bod ganddi ddiddordeb ysol mewn ystadegau a materion cyfoes, ac mae’n aeddfed ac yn graff. Fodd bynnag, mae hi’n nodi ‘nad yw’r radio na’r papurau newydd yn dweud llawer wrthych chi‘. Mae’n bosibl ei bod yn cael gwybodaeth gan ei thad oedd yn cadw tafarn ac o bosibl yn gwerthu diodydd i’r fyddin. Digon posibl felly ei fod yn cael hanesion gan y milwyr. Serch hynny, yr effaith gynyddol ar Marjorie a’i theulu sy’n taro rhywun fwyaf ac yn fwyaf dadlennol.

Wrth i’r flwyddyn 1940 fynd rhagddi, mae llawysgrifen Marjorie yn dod yn fwy brysiog ac mae ei sylwadau yn dod yn fwy personol. Mae hi’n disgrifio cyrchoedd awyr aml sy’n ‘ysgwyd ein tŷ’ a theimlwn gwir ymdeimlad o argyfwng a braw. Ar 28 Awst mae hi’n ysgrifennu: ‘Roeddent yma eto cyn gynted ag yr oedd wedi tywyllu heno, am 6 awr arall. Rydym wedi gwneud gwely dros dro yn y cyntedd’. Ar 24 Hydref mae hi yn ingol yn ysgrifennu: ‘Byddaf yn cofio fy mhen-blwydd heddiw- 8.20 seirenau … ychydig o amser oeddent yma ond roedd y difrod yn fawr. Rhai o’r bomiau mor agos.

Erbyn y Nadolig, mae llawysgrifen Marjorie yn ymddangos yn blentynnaidd ac mae’r disgrifiadau yn brin : ‘Ês i geisio siopa rhywfaint. Dim llawer y gallwch chi ei brynu y dyddiau hyn …‘ ac ar ddydd Nadolig ‘Wedi treulio Nadolig tawel iawn gartref. Dim seirenau’. Ond nid yw dyddiadur Marjorie Harding heb deimladau dwys a hiwmor. Dyddiadau mewn cylch yn fisol sydd yn ôl pob tebyg yn marcio cylch ei misglwyf ac mae hi’n cyfeirio’n aml at ei chwaer Betty, gan ddweud ar 13 Ebrill: ‘Betty wedi cael PERM i’w gwallt’. Ar ben hynny, rhywfaint o ddihangfa o erchyllterau’r rhyfel ar ffurf teithiau siopa, Betty yn cael ei derbyn i’r coleg ac, ar 7 Mawrth, siwrne i’r ‘pictiwrs… i weld Shirley Temple yn Suzannah of the Mounties‘.

Drwy gydol ei dyddiadur, mae Marjorie Harding yn cyfeirio at ei dyddiau fel rhai ‘tawel’ heb ‘ddim byd o bwys yn digwydd’. Fodd bynnag, mae hanes yn datgelu pa mor arwyddocaol y mae ei geiriau wedi dod fel mewnwelediad personol i oes na fydd byth yn mynd yn angof. Ni wyddys llawer am ei bywyd yn Ninbych-y-pysgod ar ôl y rhyfel, heblaw iddi farw ym 1997 yn Ne Sir Benfro.

The wartime diary of Marjorie Harding

The wartime diary of Marjorie Harding